A friend recently tipped me off to The little book about OS development, an excellent hands-on resource on writing a (simple) operating system from scratch. I’ve been working through the book, and it’s been an amazing learning experience.

A lot of the initial difficulty was in the tangential exercise of setting up a reasonable dev environment on my Mac rather than the inherent challenges of assemblers, interrupts, and virtual memory–though those can be plenty of “fun” as well!–so I thought I’d share a bit about how I set things up in the hope that it might benefit others working through the book on a macOS environment.

Building

The first challenge is putting together the toolchain to assemble/compile/link the various binaries that make up the kernel, boot loader, and other modules and bits. One challenge with doing this on a Mac is that the book assumes pretty deeply that you’ll be using Grub to load ELF binaries, which are not native to the Mac. I’m sure it’s possible to set up cross compiling with a custom GCC build on Mac and a handful of other carefully configured tools, but I found it much easier to just do all the compilation in a Docker container. In addition to providing a Linux runtime and fast binary installs of most of the ELF-compatible tools, this provides a complete config-as-code manifest of what’s in the core development environment.

The only prerequisite for this setup is Docker for Mac. Once that’s installed, you can clone my repo and give my setup a try. If you take a look around its structure, everything should look pretty familiar from the first chapter or two of the book–I did my best not to “give away” too much and keep it a minimal skeleton. The Dockerfile and script/* files, however, are my additions. The Dockerfile just contains a bunch of build utilities, an ISO utility, and custom-built Grub 2 (note that I’m using Grub 2 and grub-mkrescue to produce the ISO instead of the book’s Grub Legacy with a pre-built stage2_eltorito binary). I’ll explain the other scripts later. You can build a complete ISO by running docker run -v $PWD:/opt/littleosbook bellkev/littleosbook-mac make from the project root. It should go relatively quickly, as the pre-built Docker image will be pulled from Docker Hub by default.

Running

To run the OS, the book suggests the Bochs emulator, which appears to be quite popular for OS development. I tried looking around for binary installs and compiling Bochs myself on my Mac, but the experience was a bit dicey. I never really got it to run very happily. I considered running everything inside of a VirtualBox or VMware VM, but even if that’s possible, two layers of virtualization between the keyboard, monitor, etc and my OS didn’t sound fun. Instead, I opted to use QEMU, which seems to have much better cross-platform support (as well as being extremely widely used and well-maintained).

You can easily install QEMU with brew install qemu and run it with a command like qemu-system-i386 -cdrom os.iso. The script script/run-vm.sh takes care of both the Dockerized build process and running QEMU with some appropriate arguments. The QEMU “monitor” is also tied to stdin/stdout, so you can run info registers at the (qemu) prompt, and you should see EAX=00000006 (the result of the sum_of_three C function from the book).

Troubleshooting

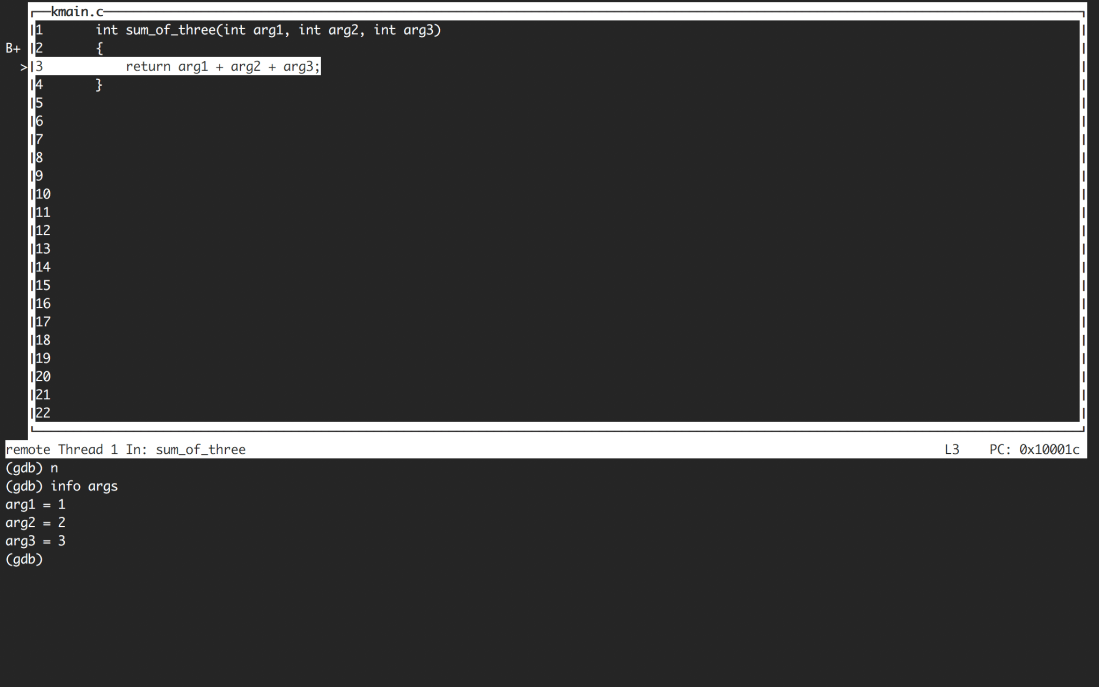

A friend that was working through the book with Bochs pointed out that Bochs has some pretty handy built-in debugging capabilities, which lead me to explore what options were available in QEMU (and kick myself for not having done so earlier). Fortunately, QEMU is no slouch in this regard either. With a couple command line flags, you can instruct QEMU to open up a TCP listener for GDB remote debugging with all kinds of symbolic debugging features for both assembly and C sources.

Like in the compilation stage, there are some binary compatibility issues with GDB on Mac and ELF binaries. Again, it seems to be possible to solve the problem with a special, cross-compiled GDB, but I opted to just run vanilla Linux GDB in a Docker container.

To set up debugging, you can run script/run-vm.sh -S. Extra args are passed through to QEMU, which interprets -S to mean “freeze CPU at startup”, giving you an opportunity to set breakpoints in functions that run very early in the boot process. The only tricky bit with the Docker setup is getting GDB to find its way to the host IP address, which is accomplished with the special docker.for.mac.localhost hostname.

The picture above shows the curses-based Text User Interface mode, which you can get into/out of by pressing CTRL-X CTRL-A. I’m sure there are lots of other GDB clients that can talk to the TCP port exposed by QEMU, and other ways to address the ELF compatibility issue, but the retro flavor of GDB TUI felt more aesthetically aligned with building a bespoke OS.

In my own environment, I finally tie the run-vm and run-gdb scripts together with a top-level script that pops open a few tmux panes so that all the various logs and tools are visible in one terminal window. That’s pretty specific to my environment though, so you’ll probably want to do fine tuning like that for yourself.

Bonus Tip: Hacking Fullscreen Mode

This last tip is arguably minor, but was extremely satisfying to figure out. QEMU has a fullscreen flag (which is used in script/run-vm.sh), but by default either using or not using this flag lead to the QEMU monitor opening behind my fullscreen terminal window (on the active monitor). The resultant clicking around and command-tabbing was surprisingly frustrating while iterating on certain bits of OS code.

I usually work with two monitors–my smaller laptop display on the side, where I’d ideally like the VM monitor to appear, and my main, big monitor. Getting the VM monitor to appear in the small display actually turned out to be pretty easy to achieve with a tiny patch to the Cocoa UI code in QEMU to make “fullscreen” mean “the main screen (that the menu bar is docked to in display preferences)”.

Conclusion and What Comes Next

That’s it for my humble summary of Mac OS Dev tips. I should end by thanking the awesome authors of The little book about OS development. They really did put together an incredible resource. I’ve also been going through the textbook by Tanenbaum that they recommend, and it’s way more readable and exciting than it would’ve been before doing any of the practical exercises in the little book.

As a teaser for a possible future post, I’ll add that if you have any interest on getting your OS to run on actual hardware, you may want to look into UEFI rather than creating an ISO and doing legacy/BIOS booting. Manipulating “raw” devices like USB sticks in the ways needed to make traditionally bootable drives on a Mac is a bit of a pain. UEFI is also generally more modern, robust, and well-documented. I recommend this high-level overview of UEFI as a starting point, and Tianocore and OVMF for BIOS images that can be used with QEMU to test out a UEFI setup. I’m still playing with all of this though and don’t feel quite qualified to give more concrete pointers than that … yet!